My trip to Boston was meant to support a good friend whose work as a playwright was having a world premiere at the Boston Arts Center. Boston is a city known for its significant role in the American Revolution, leading to the independence of what is now known as the United States. When thinking about this trip, I initially wanted an overnight stay – arrive before the show and return to NYC the next day. However, due to the insistence of friends and colleagues, I decided to stay for another day, to do some sightseeing, considering the city’s historical significance. At the same time, it is the gateway to Harvard University.

Before my travel, I was eager to do a heritage walk – to trace the American Revolution via Boston’s monuments and historical buildings. I was also keen to visit Harvard University, a prestigious, private Ivy League university, founded in 1636, and one of the leading higher learning institutions with a very high global reputation. Many of the notable scientists and artists are from Harvard. But the visit to Harvard never materialized. While searching for the best things to do in Boston, I came across Salem and discovered it’s about 45 minutes away via train from Boston’s North Station. Coincidentally, the hotel I would stay at was a two-minute walk from the train station.

I needed to see Salem. It was an important place because the first American play I read was about Salem. It was Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, which takes place in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692 during the Salem witch trials. It tells the fictionalized (or inspired by true events) story of young Salem women who falsely accuse villagers of witchcraft, leading to mass hysteria, 200 arrests, and 19 executions (the mass hysteria, 200 arrests, and 19 executions are true. Although there were 20 executed. 19 were hanged and 1 was executed by “pressing”). Arthur Miller wrote the play during the 1950s McCarthy era as an allegory, drawing parallels between the witch trials and the political persecution of alleged communists in his time.

I went to Salem to have a more critical picture of what happened during the infamous Salem Witch Trials of 1692. While I wanted to do the tour on my own, I ended up hiring a tour guide – a local expert, so to speak to tell me more about Salem and the trials as we went on with the tour.

The Salem Witch Trials in 1692 were a period of intense religious hysteria in Massachusetts. Over 200 were accused, 19 innocent lives were hanged, and one was pressed. The trials were characterized by a lack of due process, with accusations often based on circumstantial evidence and testimonies of the “afflicted” girls. My tour guide told me that somehow the witch accusations started in the house of a minister named Samuel Parris, whose daughter’s nanny, Tituba, was from the Caribbean.

Having a different religion, Tituba was a practicing voodoo. One voodoo practice that started the hysteria was her ability to foretell the future husbands of girls – by breaking an egg into a glass of water and identifying the shape and form that the egg produces (i.e., the shape of the egg in the water shows a picture of a merchant). Eventually, this became Parris’s daughter’s favorite pastime and that of her girlfriends. However, one of the friends saw the image of the devil in the glass, which led to the hysteria. Eventually, Tituba was made to confess about being a witch. She never went to trial because of the admittance and never executed because the Puritans believed that God has his own way of punishing Tituba for admiting such wickedness. She was placed in the dungeon nevertheless.

To avoid any accusations of witchcraft, the girls started accusing people of having been “acquainted with the devil.” This led to the arrest of 200 people. It was only recently, in the 1990s, that the State of Massachuesstes acknowledged the witch trials as historically significant. Though the respected minister Cotton Mather warned of the dubious value of spectral evidence (or testimony about dreams and visions), his concerns were largely unheeded during the Salem witch trials. Increase Mather, president of Harvard College (and Cotton’s father), later joined his son in urging that the standards of evidence for witchcraft must be equal to those for any other crime, concluding that “It would be better that ten suspected witches may escape than one innocent person be condemned.”Trials continued with dwindling intensity until early 1693, and by that May Phips had pardoned and released all those in prison on witchcraft charges. But another version of the story: the witch trials were discontinued because the governor’s wife was already accused to be “seen with the devil.”

In January 1697, the Massachusetts General Court declared a day of fasting for the tragedy of the Salem witch trials; the court later deemed the trials unlawful, and the leading justice Samuel Sewall publicly apologized for his role in the process. The damage to the community lingered, however, even after Massachusetts Colony passed legislation restoring the good names of the condemned and providing financial restitution to their heirs in 1711.

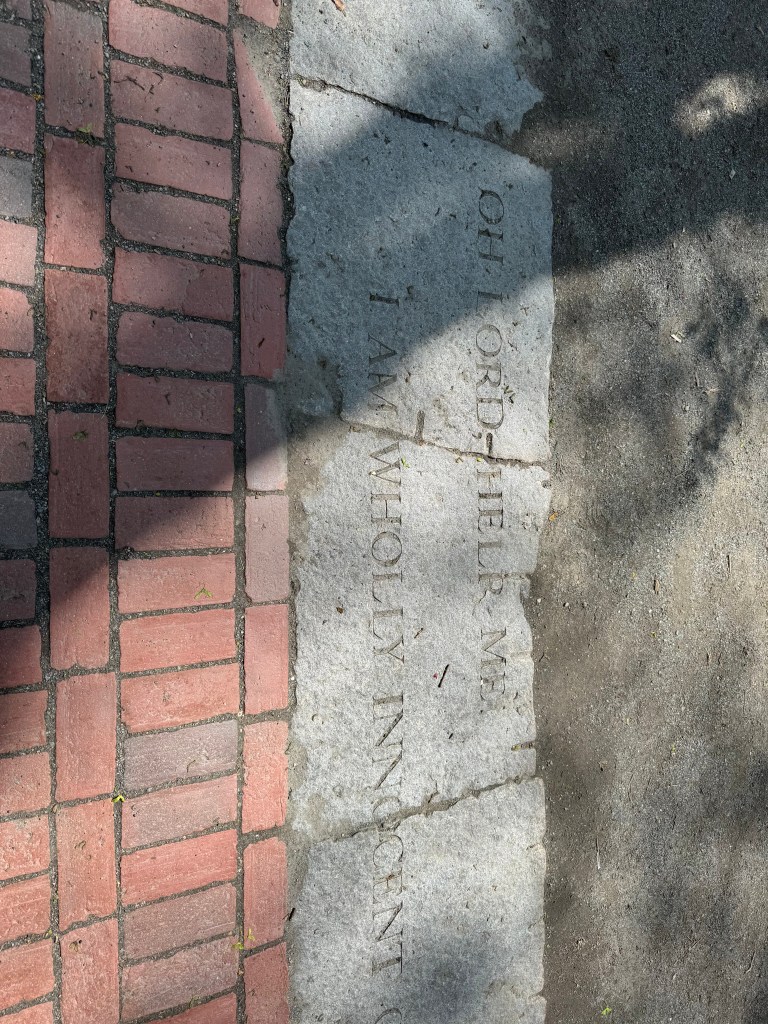

It was only in 1986 when Salem decided to create a permanent memorial for the victims of the witch trials, unveiled on 5 Aug. 1992. The memorial is very simple yet very emotive and dramatic. Granite walls surround three sides, with granite benches representing each victim. Etched on these benches are the names, means and date of execution. On the entrance – words of the accused taken from the court transcripts are present. Noticable are the incompleteness of the sentences – representing lives cut short and the authorities’ aloofness to the claims of innocense. While these individuals are now finally recognized, unfortunately, the 20 teenagers who made all the accusations, to this day, are not held accountable.