ʙᴀᴛᴀʏ ꜱᴀ ᴍᴀɪᴋʟɪɴɢ ᴋᴡᴇɴᴛᴏɴɢ “𝘏𝘰𝘸 𝘙𝘰𝘴𝘢𝘯𝘨 𝘛𝘢𝘣𝘢 𝘞𝘰𝘯 𝘢 𝘙𝘢𝘤𝘦”ni Dean Francis Alfar

ᴀᴅᴀᴘᴛᴀꜱʏᴏɴ ɴɪɴᴀ Rody Vera at Maynard Manansala

ᴅɪʀᴇᴋꜱʏᴏɴ ɴɪɴᴀ José Estrella, Issa Manalo Lopez, at Mark Daniel Dalacat

ɪᴛɪɴᴀᴛᴀᴍᴘᴏᴋ ꜱɪɴᴀ Kiki Baento, Peewee O’Hara, Meann Espinosa, Victor Sy, Jojo Cayabyab, Aldo Vencilao, Garnet Acala, Dyas Adarlo, Danzar Dellomas, Moi Gealogo, Lia Lilagan, John Lucing, Eyn Matorres, Sam Marasigan, Jien Santiago

ᴅʀᴀᴍᴀᴛᴜʀʜɪʏᴀ: Sir Anril P. Tiatco at Jonas Gabriel M. Garcia; ᴅɪꜱᴇɴʏᴏ ɴɢ ᴇɴᴛᴀʙʟᴀᴅᴏ: Mark Daniel Dalacat; ᴅɪꜱᴇɴʏᴏ ɴɢ ᴋᴀꜱᴜᴏᴛᴀɴ: Carlo Villafuerte Pagunaling; ᴅɪꜱᴇɴʏᴏ ɴɢ ɪʟᴀᴡ: Barbie Tan-Tiongco at Mykee Ababon; ᴅɪʀᴇᴋᴛᴏʀ ɴɢ ᴍᴜꜱɪᴋᴀ ᴀᴛ ᴅɪꜱᴇɴʏᴏ ɴɢ ᴛᴜɴᴏɢ: Angel Dayao; ᴅɪꜱᴇɴʏᴏ ɴɢ ɢᴀʟᴀᴡ: Carlon Matobato; ᴅɪʀᴇᴋꜱʏᴏɴɢ ᴘᴀɴᴛᴇᴋɴɪᴋᴀʟ: Maria Loren Rivera; ʟɪᴛʀᴀᴛɪꜱᴛᴀ: Paw Castillo; ᴅɪꜱᴇɴʏᴏ ɴɢ ᴘᴏꜱᴛᴇʀ: Jada Bartolome; ᴛᴀɢᴀᴘᴀᴍᴀʜᴀʟᴀ ɴɢ ᴘʀᴏᴅᴜᴋꜱʏᴏɴ: Camilo De Guzman; ᴛᴀɢᴀᴘᴀᴍᴀʜᴀʟᴀ ɴɢ ᴇɴᴛᴀʙʟᴀᴅᴏ: Rodney Barnes at Rigel Hechanova; ᴘᴜʙʟɪᴄɪᴛʏ: Marc Stanley Mozo at Holden Kenneth Alcazaren; ᴍᴀʀᴋᴇᴛɪɴɢ: Kate Ashlyn Dayag-Nonay; ꜱᴘᴏɴꜱᴏʀꜱʜɪᴘ: Ma. Theresa De Guzman; ᴍᴀɴᴀɢɪɴɢ ᴅɪʀᴇᴄᴛᴏʀ: Tess Jamias; ʙᴜꜱɪɴᴇꜱꜱ ᴍᴀɴᴀɢᴇʀ: Anna Gamboa; ᴅᴜᴘ ᴘʀᴏᴅᴜᴄᴛɪᴏɴ ᴍᴀɴᴀɢᴇʀ: Archie Clataro

#DulaangUP46 #DUPRosangTaba #BabaeAkoKayaKo

WE OPEN TONIGHT

Here is our dramaturgical notes, musings based on the first run of Rosang Taba, staged at the UP Theater Main Stage in March and April 2023.

AMA. Sandali nga. Ang layo na ng narating natin. Ang dami mo nang pangarap, ang taas na ng iyong lipad. Samantalang ang tanong ko’y kung paano? Paano mo tatalunin ang pinakamatulin, pinakamaliksi, pinakamayabang na Ispancialong Ser Pietrado?

ROSA. May naisip na po akong paraan.

AMA. Sa karera?

ROSA. Opo. At kung manalo ko.

AMA. Kung manalo ka? Sa tingin mo ba’y mapapalitan niyan ang pagtingin nila sa Kataong tulad natin? Sa isip mo ba, mababago mo ang kaisipan nila?

ROSA. Di ko alam kung mababago ko ang isip nila. Umaasa akong mababago ang isip natin.

AMA. At kung matalo ka?

ROSA. Hindi pa po ba talo tayong mga Katao, Ama? Matagal na. Dami niyo na ngang nalimutan sa ating nagdaang karangalan. Pero… kung manalo po ako? Tulad ng mga bayani sa kuwento niyo?

AMA. Hindi ito kuwento, Rosa! Alam mo ba kung ano ang nakataya?

ROSA. Opo. Ang aking pagkatao.

This excerpt is from the play you are going to see in a few minutes or the play you saw a few minutes or an hour ago or may be even last year at the UP Main Theater Stage. Here, the titular character Rosa responds to her father’s skepticism about her winning the race from the fastest man in town: the Ispancialo (reference to Spanish) Jaime Alonzo Pietrado ei Villareal (Pietrado). Rosa’s father’s distrust is due to her physical condition: she is a big woman, hence the moniker Rosang Taba, which is literally translated as “fat rose” in English. Moreover, her father is also doubtful because Rosa’s challenging Pietrado in a race may bring additional embarrassment to the family and to their hometown, Lupang Sinilangan.

The excerpt above speaks of three things. First, Rosa embodies the maxim everything is a matter of perspective, especially in the writing of history where usually the victors are placed on a privileged position to tell their stories. In this short conversation, we see Rosa’s plight for urgency to share their side of the story even if people think they are history’s losing side. Rosa, in the excerpt, implicitly exclaims every story has many sides.

Second, it speaks about the dynamic relationship of remembering and forgetting, and how both are manipulated by those conceived as authority. The short scene invokes how those in power easily create oppositions such as civilized and the savages, the strong and the weak, the winners and the losers, the able and the helpless, with an agenda of identifying the supposed subject as the other side of the opposition: the savages, the weaklings, the helpless, etcetera. Hence, these signifiers become part of the subject’s identity due to interpolation. Like in the case of Rosa’s family, her parents have long been convinced that they are the uncivilized and the unlearned because the colonial masters have been constantly impinging these into their heads via laws, education, traditions, policing, and other ideological and repressive state apparatuses.

Finally, it invites us to think of mythmaking as a form of decolonization via strategic essentialism. Borrowing from Gayatri Spivak, strategic essentialism refers to the process of marginalized communities to essentialize themselves in moments when they need to assert themselves from others and to unite for political reasons. In Rosang Taba, mythmaking becomes a productive way to assert the personal and the membership to a collective. This assertion is necessary because it illustrates how the marginalized or the subaltern responds “enough is enough” to the dominant authority’s ongoing denial of their ontologies and epistemologies by pushing something else as valid and absolute.

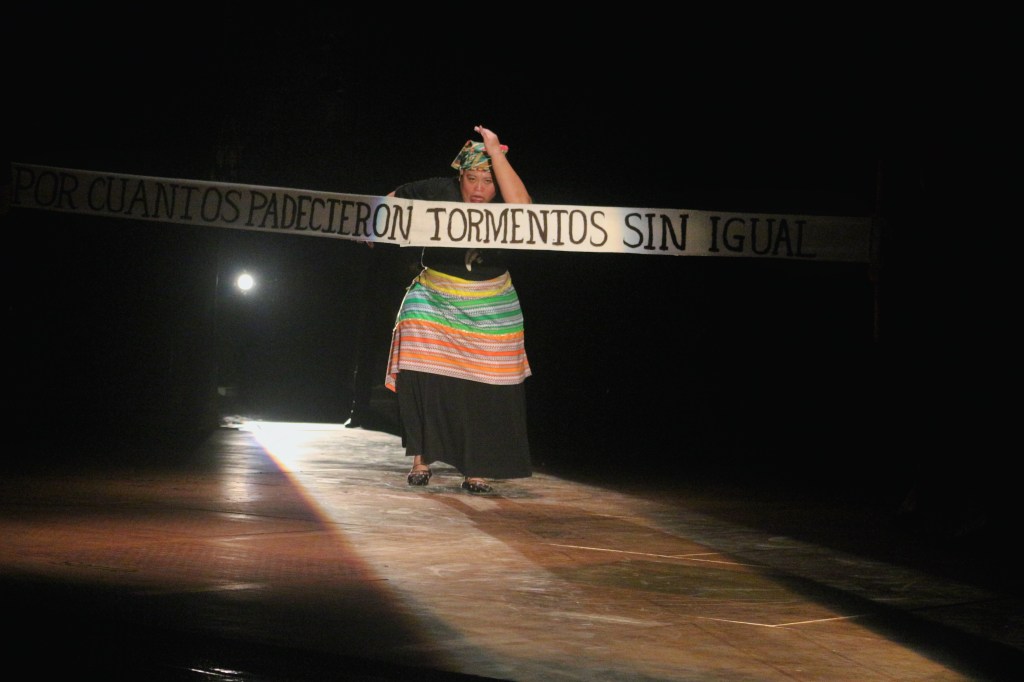

Originally staged on the occasion of the National Women’s Month in the Philippines, directors José Estrella, Issa Lopez and Mark Dalacat collaborated with playwrights Rodolfo Vera and Maynard Manansala to bring the children’s story to a theatrical public at the Main Stage of the University Theater in Quezon City, Philippines. Rosang Taba was originally conceived in 2020 during the global lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Rosang Taba was intended to be a recorded performance. With the theaters slowly returning to “normal,” the team behind the adaptation decided to cancel the planned 2022 virtual staging and opted for an intimate live performance that opened on 26 March 2023 and had a successful two week run until 2 April 2023.

Rosang Taba begins in the present-day colonial capital city of a country named Lupang Hinirang that resembles the Philippines. The audience in the theater-in-a-round space are brought to an eatery called Mama Rosas, which is managed by Rosa’s three great-great granddaughters. During the colonial era, Rosa was the celebrated cook of the Governor General. At present, the eatery is popular not only because of its delicious food, but also because of the hospitality of the hostesses, who every so often retell the story of their lola (literally, grandmother) Rosa. Particularly, the patrons are always eager to listen to how Rosa challenged and eventually won a race against the Ispancialo’s proud and arrogant commandant Pietrado to patrons in songs and dances. The race is important for the granddaughters because it paved the way for Rosa and her family to buy their freedom from the Governor General and used a portion of the price money to start the food business.

The initial run of the play was well received by audience members who consensually agreed that Rosang Taba was a celebration of pride and it reflected what it means to be different. Social media postings also considered it as a play that dealt with feminist concerns particularly on body issues. Others saw it as a political piece, especially the association of rosas (read here as pink) being the official color of former Philippine Vice President Leni Roberedo’s campaign during the 2022 Presidential Election. National Artist Virgilio Almario (Literature) alleviated the piece by affirming its necessity in this era of post-truth. As Almario wrote in his social media account, “Rosang Taba is the persona who despite the force of historical revisionism, is here to tell the real story.”

The dramaturgical team of the play agree that Rosang Taba participates in different conversations like feminism, postcolonialism, body studies, historiography, art and theatre practice. However, the team is also convinced that the centerpiece of the play is its potential for a decolonized dramaturgy. Particularly, the team is conscious dramaturgically, that the play pushes the specter of colonial trauma in the present to appreciate the glorious pre-colonial past. The dramaturgical team is also conscious that Rosang Taba has to perform the repertoire as a testimony that despite what the colonial masters have written about the natives in the archive, we cannot dismiss them as authorities of culture-making. They embody local ontologies and epistemologies. The dramaturgical team has also envisioned to transform the audience from being spectators to being witnesses or as memory studies scholar Derek Goldman notes in a different context, the audience members perform a conscious act of witnessing, a transference of accountability to acknowledge that something substantive has occurred in which all those present are now implicated, and that can never be unseen.

Generally, the relationship of theatre, mythmaking and cultural memory is explored in the play. In the context of historiography, mythmaking is often perceived as an overflow because of its hyperbolic nature and its potential for disinformation. In the case of the play, the overflow is presented to be necessary. Rosang Taba’s overflow is a strategy of decolonization via strategic essentialism. In the end, Rosang Taba is an allegorical representation of the past that affects the present and projected toward the future: an aspiration for a better community tied by a cultural imagination of a united people based on shared ancestry and history.

Thank you for joining us in this theatrical attempt of decolonization. For those who have already seen the play earlier once, may be twice, or several times, thank you for having accompanied us in this historical and necessary mythmaking.